By Nuri McBride

Beauty standards at first seem like the natural by-product of society, just an aggregate of society’s aesthetic opinions and sexual tastes. Yet, in reality, beauty standards are a set of norms that reinforce the gender and class status quo in a patriarchal society. It is a handy implement in the toolbox of oppression. Beyond the insidiousness of reducing women to their physical form and celebrating one narrow interpretation of beauty at the expense of the vast range of feminine experiences, beauty standards also serve as the physical manifestations of prescriptive female behaviour. If society’s beauty standard dictates a ‘proper’ woman should have pale skin and wear a crinoline that makes it near impossible for her walk through a doorway, chances are, that is a society that believes a woman’s place is in the home. So what does it say about a culture when the height of beauty is to be slowly dying of a horrific illness?

That is exactly what happened throughout the Western world from the 1780s to 1880s during the Georgian-Victorian obsession with Tubercular Beauty. Now, women have been accidently harming themselves in the name of beauty for aeons from lead-based cosmetics, to arsenic skin tonic to unhealthy fasting diets. The Victorian preoccupation with Tuberculosis was different. It was the romanticisation and sexualisation of tubercular symptoms and ultimately dying women.

Tuberculosis was not new to the Victorians. It is an ancient and devastating illness, but the rise of the Industrial Revolution, the urban sprawl from the Great Rural-Urban Migration, and poor health regulations created fertile breeding grounds for TB to become endemic in cities like London, Edinburgh, Paris, and New York. TB affects both men and women and was rampant in the poorly ventilated slums of cities like Victorian London. Yet when TB attacked young women of the upper classes, it was treated decidedly differently than when it struck poor women. The vector for TB was not understood until 1882, and its prominence in the upper class gave it a particular cache. TB was thought to be hereditary proclivity to illness, not a disease itself. So unlike plague or sexually transmitted diseases, there was no moral judgment on those afflicted, nor fear to be around them. It was not new so there was no social panic or increased religiosity, which tend to accompany new contagions. As a respiratory/pulmonary illness, it also saved the sufferers from the indignity of bowel-based ailments like Dysentery or Cholera, at least at first. This all lead to circumstances where society did not fear Tuberculosis and could develop a warped appreciation of it. Tuberculosis does not always kill quickly, it’s often a slow and steady decline to drowning in a pool of your own blood and sputum. However early symptoms seemed to heighten already established beauty standards of the time, and a wealthy young woman could waste away for years before the horrible end came. In the meantime, poor circulation turned fair complexions ghastly white. The blue veins and translucent fragile skin were treated as a crystalline delicacy. The constant low fever kept the cheeks and lips flushed with a rosy hue and the eyes wide and watery. Patients would waste away growing ethereally thin. The constant coughing made it agonising to speak above a whisper and many sufferers stop speaking altogether.

It may be important to note here that these established beauty standards were deeply influenced by the European aristocracy, who by this time, were suffering from haemophilia and a host of other genetic conditions. They were not the healthiest bunch on the planet. For instance, the Hapsburg Jaw (a form of genetic mandibular prognathism) was considered a sign of great male beauty even though it reached the point in some lines of the family that individuals could not fully close their mouths.

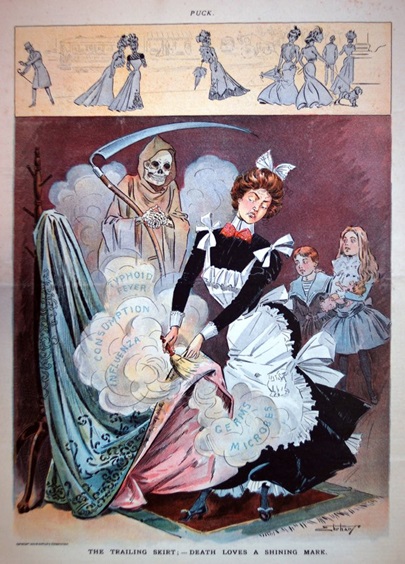

While the fragile appearance of royals has always been coveted the physical manifestations of their illnesses were not. That is where the rise of the Tubercular Beauty differs. A woman suffering from Tuberculosis would have difficulty breathing, simple tasks would put her under great strain, she would constantly be cold in her extremities and prone to fainting. This fragile state was praised as the height of femininity. This gave rise to the stereotype of the breathless fainting woman that needed to avoid stimulation. It was reinforced by the trend (inspired by tubercular thinness) for long-line corsets and the fad of tight-lacing to achieve as thin a waistline as possible. The skirts also kept getting bigger to accentuate the smallness of the torso. As women of the upper and middle classes were not expected to physically move much in their delicate states, the dresses took on monumental proportions. It also turned lovers into paternal caretakers and turned women into invalids. No man needed to worry if his Tubercular Beauty was home in the evening, where else could she be in her state, where else could she go in that dress?

With the illness and death of John Keats and Robert Louis Stevenson, Tuberculosis became associated with civilisation, sensibility, the arts, the Romantics and (in men) it was the illness of geniuses. In women, it became a tragic beauty. The Pre-Raphilite painters had a disproportionate number of muses that died of consumption. It was not seen as a contagious disease in the upper classes but rather the physical manifestation of a delicate and civilised nature. In fact, if a woman was already beautiful and refined she was thought to be of particular risk to succumb to TB. Not only were sick women fetishized, but healthy women were also urged to emulate this breathless pale beauty. Even dying women were met with a romantic glamorisation of their circumstances. The dying’s fear and far-off contemplations gave an ethereal otherworldliness adored by poets. The dying woman becomes tragically seductive by her finite lifespan. This was a beloved trope in both writing and stage productions of the time. TBs long folk association with vampirism also gave the infected women a certain fairy-crossed, cursed glamour.

The tragic star Mimi in Puccini’s La Boheme (1896) and Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata (1853) both had TB. Antonia in the opera The Tale of Hoffman (1816) has TB and is (spoiler alert) forced to sing herself to death. In the novel La Dame aux Camelias or Camille (1848) Alexandre Dumas’ Marguerite dies of Tuberculosis. Katerina in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866), as well as Ippolit and Marie in The Idiot (1869), meet their ends via consumption. Fantine in Les Miserables (1862) has a horrible low-class death via TB, but Little Eva’s death in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) is practically angelic.

“For so bright and placid was the farewell voyage of the little spirit, by such sweet and fragrant breezes was the small bark borne towards the heavenly shores,that it was impossible to realize that it was death that was approaching. The child felt no pain, only a tranquil, soft weakness, daily and almost insensibly increasing; and she was so beautiful, so loving, so trustful, so happy, that one could not resist the soothing influence of that air of innocence and peace which seemed to breathe around her.”

Even in a modern interpretation of Tubercular Beauty, the charming but ill-fated Satine in the Moulin Rouge (set in 1899 Paris) manages to sing throughout the movie, though she is coughing up blood, and dies in her lover’s arm still pale, rosy-cheeked and gorgeous.

Even when real women died during this time, it seemed to only add to the glamour of the contagion. The apocryphal tale behind John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1852) is that Millais had muse Elizabeth Siddal float in an icy bathtub for hours while he painted her as the drowned Ophelia. Siddal, ever the faithful muse, said nothing, weakened, and developed the Tuberculosis that would kill her ten years later (though the laudanum addiction probably helped).

The tragic and beautiful Bronte sisters were decimated by consumption but it only adding to their books a new layer of dark glamour. Princess Amelia, daughter of George III, was another great beauty succumbed to TB at only 27 and her final days are written of as ethereal and otherworldly. Her brother George IV requested a death mask be made to preserve her beauty.

Two eminent modern saints lived and dead as young tubercular women at this time. Saint Therese of Lisieux died at 24 and is second to only Saint Francis of Assisi as the most popular saint of the modern church. As well as Saint Bernadette Soubirous who died of TB at 35 and is known for receiving a Marian apparition to build the pilgrimage site at Lourdes. Even though these saints were virginal and not tragic love interests their illness, weakness, and degeneration through TB became part of their spiritual legacies. Legacies that emphasised their gentleness, spiritualness, physical suffering and femininity.

So why aren’t we all carrying bloody hankies and flopping onto fainting couches? Three reasons, firstly in the 1850s doctors began to believe Tuberculosis was contagious. This arose mainly due to acute epidemics in Paris, London, Chicago, and New York that made it impossible to ignore. When hundreds of people are spreading an airborne illness with an 80% death rate, it becomes hard for composers to find any poetic charms in said illness. Secondly, the restrictive fashions associated with the Tubercular Beauty were killing women. The massive crinolines had a reputation for getting picked up by strong updrafts and throwing women into the sea. The weight of their garments would cause women to drown. More prevalent however was the fire hazards these dresses caused. It was estimated in 1863 by the journalist Petko Slaveykov that between 1850 to 1860 nearly 40,000 women died worldwide from their dresses catching on fire. The famous Dr Mütter spent the majority of his career perfecting plastic surgery techniques for women that were engulfed in their dresses and survived. Thirdly, from the 1850s to the 1880s Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch initiated the Golden Age of Bacteriology. The Miasma Theory was debunked for good by 1880. In 1882 Koch identified the bacteria that causes Tuberculosis. In 1890 viruses were discovered and public health turned to sanitation and immunisation to try to thwart the epidemic.

Whole cities were scrubbed clean, the first modern public health regulations were drafted, and the public taste turned firmly away from the Tubercular Beauty. Women were urged to engage in light exercises, to swim, visit the sea and sanatoriums. A healthy glow, a bit of colour, and a bit of meat on one’s bones now were seen as good things. The first social and medical rebellions against the restrictive Victorian corsets arose. Women began to use bicycles. Even fabrics changed. The heavy brocaded fabrics once popular in dressmaking could not be washed, only aired and brushed down. These once coveted dresses were now seen as cesspits of bacteria, plainer, but washable, fabrics were preferred for day to day garments. Even the fancy muttonchop sideburns and pomaded moustaches of the time fell out of fashion due to fear that they harboured untold legions bacteria.

I see the completion of the aesthetic rejection of the Tubercular Beauty in the Garcon style of the Flappers. The Flapper utterly rejects the passive femininity and domesticity of her mother and grandmother’s generations through her short hair, Chanel suntan, party-lifestyle and an un-corseted aesthetics that was based on sportswear, encouraged movement, and was made of practical jersey. The Tubercular Beauty became the pinnacle of a certain type of repressive beauty standard. A beauty standard that required the complete physical and social control of women. The downfall of the Tubercular Beauty was because woman began to demand the ability to be able to move their bodies in their clothes, eat, and not be forced to hide from sunlight. In a way, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. First, they took the corsets off, then they picked the bicycles up, and then they started to demand the vote. However, it’s important to note that women of colour and the poor did not have the privilege to romanticise consumption and waste away on divans like tragic heroines and even as these beauty standards changed they still found themselves excluded.

While the downfall of Tubercular Beauty was a good thing, the Garcon look was only an aesthetic reaction that is as limiting and exclusionary as any other beauty standard. Yet as we fight for body positivity, pluralistic beauty, and the end of reductionist beauty standards it’s important to realise how far we have come; and, with that history in mind, forge a better future where all forms of beauty are celebrated.

Leave a comment