By Susan Elaine Jones

How many times have you seen a real human skeleton? Probably quite a few times. Many museums have one on display somewhere. Safely locked behind glass. How many times have you touched a real human skeleton? My guess is not much or never.

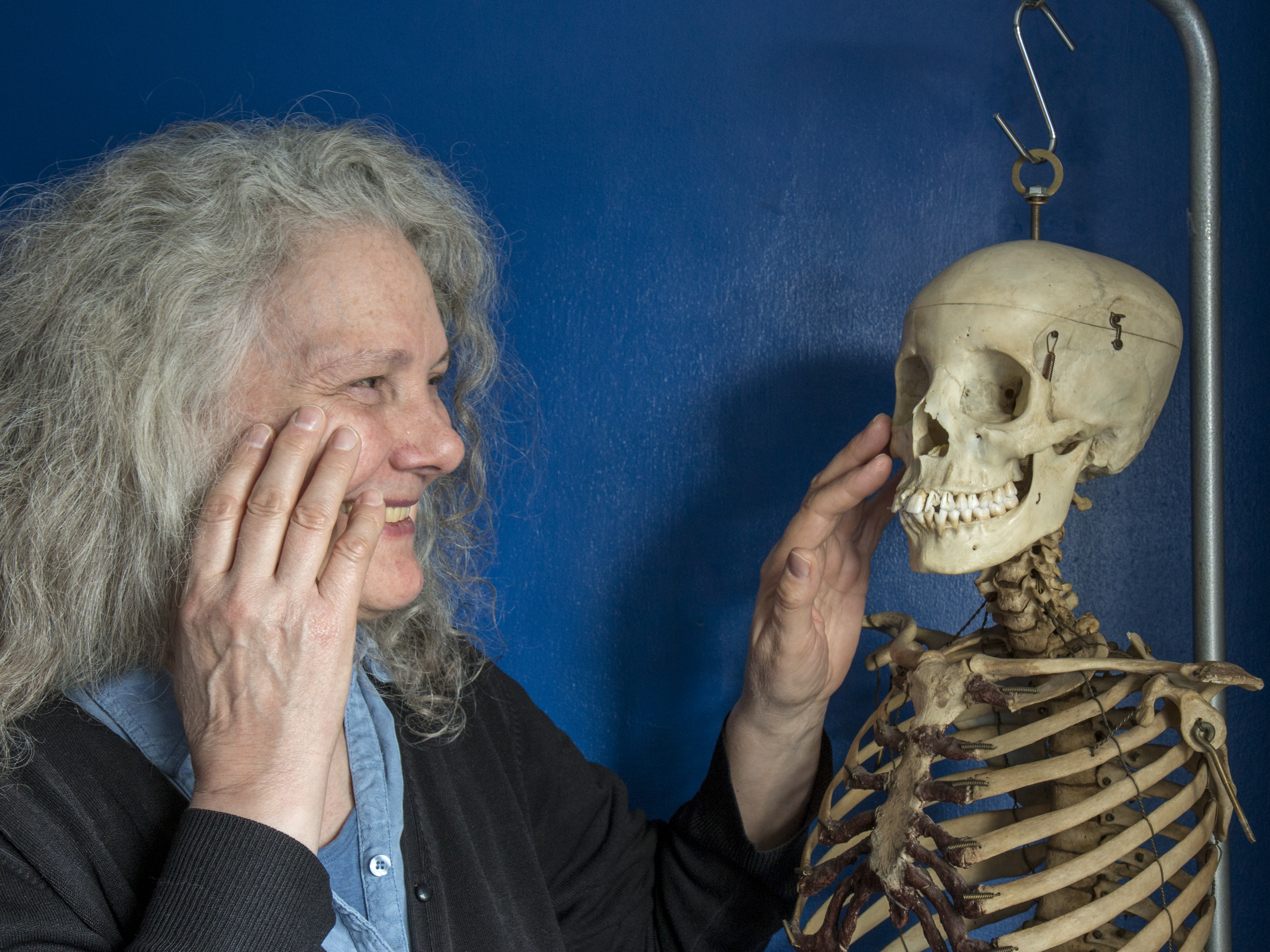

Yet touch has a very direct communication to our feeling of ourselves. Indeed, whenever I see someone touching a skull for the first time, they inevitably begin to touch a bone on the skull and try to find that same structure through their flesh on their own face: Feeling for a cheekbone, the line of the jaw, the angle in the eye orbit.

That was my first reaction, a few years ago now. Searching for the traces of my bones that would tell some future archaeologist that I was born female not male, of European ancestry, enjoying a tasty but soft sugary diet and with a jaw too small to accommodate my wisdom teeth.

But it was more than that. Looking into the familiar face of a skull, somewhere deep inside I realised that someday, I would die. And sometime in the past, this person must have faced that prospect too.

“Looking into the familiar face of a skull, somewhere deep inside I realised that someday, I would die. And sometime in the past, this person must have faced that prospect too.”

My own journey to wanting to touch skulls was purely scientific. One museum skeleton notice explained how to tell a male skull from a female one: it has a larger mastoid process, a squarer jaw, a more rounded eye orbit, more pronounced eyebrow ridges… But there was only the one skull to look at! How can you make those comparisons with only one skull? I searched local museums and photographed what I could for comparison, but the angles were never the same, the viewpoints limited, and sometimes the sex wasn’t even labelled.

But I started to notice something obvious.

They were all different.

They were all individuals.

I know I should have realised that, but somehow it came as a shock to see the unique beauty of every single one shining through. I’ve filled a website with hundreds of images of real skulls, each one, and each angle, showing something different.

The image of a skull is so popular now, you can’t walk down a street without seeing it on a bag or a scarf. But they are stylised, cartooned versions of the real thing. There isn’t a “person”, as was, behind them. Now, every skull I see, I look for clues to the person it was. And I feel privileged when I find something unique about them that even they didn’t know about themselves. A skull with beautiful suture lines that look like a meandering river from space. A cranium with deep grooves inside, where the arteries lay. A genetic trait where the frontal suture line never heals over and means families can be traced together in graveyards. I have one of those sutures, seen on my CT scan. They could be my relatives!

“Now, every skull I see, I look for clues to the person it was. And I feel privileged when I find something unique about them that even they didn’t know about themselves.”

Since that first experience, I have become passionate about giving other people that same opportunity I had: To touch a real human skull, and so make a direct connection to own mortality.

Emerging from the age of death denial, we still don’t see dead remains easily and have become divorced from our own history where handling human bones was a positive act of remembrance.

Sometime, after the initial nerves, after talking about the science, after finding common features between a skull and a face, people’s stories start to spill out: One person told me about burying their cat in the garden after it was put down, now fearing turning over the flowerbed every year. Another told me how the family agonised and argued in arranging a funeral for his grandfather, with no idea what he would have wanted, to only discover that they got everything wrong. He had written very explicit wishes for his funeral in his will, but didn’t tell anyone about it, and they didn’t read it until too late.

That’s the point I find most rewarding: Letting people find a space where they feel safe to talk about these things. Then, to have the chance to think about what they want for themselves, or how to handle things better in the future. Which is why, in addition to sharing photos of skeletons, I organise events where the public have the opportunity to meet them in person.

“Letting people find a space where they feel safe to talk about these things.”

On Saturday the 18th of May 2019, Cambridge City Crematorium will be hosting my next event, titled “Things to do when you’re dead”. It is sponsored by the Museum of Cambridge and the Cambridge Museum of Technology with the specific aim to capture people’s memories, thoughts and opinions on death and dying. As well as trying to keep the mood light with games and good cakes, there will be skeletons and skulls on hand, with artists, archaeologists, osteologists, anatomists and volunteers who are all ready to listen and let people talk about their thoughts on mortality. I hope, like Death Café, and previous events I’ve organised, in addition to the inevitable dark moments and dark humour when first opening up, it will offer a positive, life affirming chance to talk about our inevitable mortality, and how to best enjoy life before then.

Susan began photographing in 2003. Her artistic expression was liberated by becoming ill with ME/CFS. This long term illness changed her view of life and what is important.

Susan now explores aspects of health, mortality and experience. Whenever possible she goes to explore the wonderful treasures on display in the many amazing museums in the country, and occasionally blogging about them.

Also considering the impact of long term ill health, and the insular isolation from society that it imposes, she considers life and death and what it means to her. She co-organised the Dying for Life event in Cambridge in May 2017, and spoke at the Death and the Maiden conference in July 2017, examining the depiction of human remains in art through the centuries.

Leave a comment