Archaeology, the study of past human cultures, is inherently linked with the study of death. Even if one’s research in the field isn’t explicitly tied to human burials, it’s a fairly well known fact that everyone we study has died. I came into this field with vague ideas of how I wanted to proceed, and every one of my plans were tossed out the window after my first field school in Ireland. We surveyed rural Catholic and Anglican cemeteries and churchyards, and I haven’t swayed from the burial-related course since. However it wasn’t until beginning my graduate degree that I became more connected with the Death Positive movement in the Western world.

Primarily, my current research examines burial landscapes rather than specific burial practices. I study the placement of burial grounds and how that relates to the settlement layout in British settlements from the 17th-century in colonial North America and Newfoundland. Without regard for the indigenous peoples who inhabited this land before they arrived, English immigrants to North America build settlements which were free from the confines of hundreds of years of occupation of their own people, constructing towns that suited their needs at that moment. My research encompasses 63 sites, looking for patterns in the choices made when creating a new burial ground. I conducted a statistical frequency analysis which generated the more popular or probable locations for burial grounds in the areas surveyed. Examining the data over all, and then by regions settled by like-minded people, some patterns began to emerge as to popular placements in British North American towns, and I applied these results to Ferryland, Newfoundland to help narrow down the search for the 17th-century burial ground at ‘Colony of Avalon’.

“She was an amazing woman, and being able to add to her mostly unknown life by marking her grave would be an honour.”

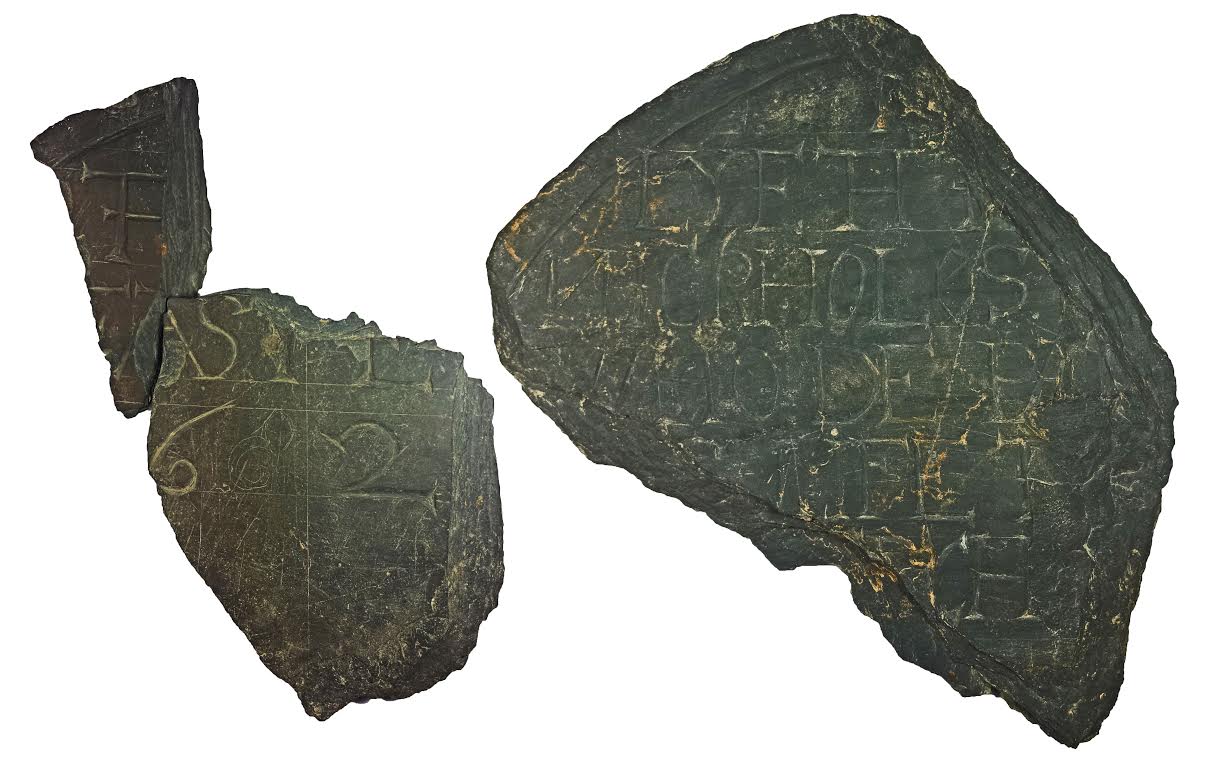

The town of Ferryland, on the Southern Shore of the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada, was founded in 1621 by Sir. George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore. The original settlement had a protected harbour, and with easy access to slate outcrops, constructed many of the early buildings completely from stone! In 1628, over a particularly rough (and Calvert’s first) winter on the Shore, ‘nyne or ten people dyed’, wrote Calvert in a letter back to the King of England. What is particularly interesting to me at this part of the story is that Calvert’s own home at Ferryland was also acting as the hospital. He would have been writing his letter upstairs, probably by the light of the only fireplace, while downstairs his settlers were dying in his own home… and he’s still not able to write how many had gone. Also, he never mentioned what they did with the bodies, and there has been no surviving document to mention further deaths at Ferryland. Three fragments of gravestones have been found at the site in 17th-century contexts, but these are broken pieces with no dates or clues as to where they came from…however they are proof that gravestones were made here, and the likelihood that they came from an organized burial ground is very high. Based on the statistical analysis, the most probable locations would be on an elevated landform, in a central or eastern location from the town itself. I’m specifically looking for the burial ground that came from this early period of British habitation, 1621-1638~, but there is a later burial which would surpass all others! Lady Sara Kirke, the wife of Sir. David Kirke who ran the settlement at Ferryland after Calvert’s departure, continued to run the settlement after her husband’s imprisonment and death, despite having had the means to return to England. She was a respected business owner and credited by many to be North America’s first entrepreneur, and she lived and worked at Ferryland until her death in 1683. The stories tell that she was buried near her plantation (the settlement) on the Downs, the peninsula on which Ferryland sits. She was an amazing woman, and being able to add to her mostly unknown life by marking her grave would be an honour.

In the summers of 2016 & 2017, I gathered teams of volunteers for my excavations of several of the locations that were suggested by the statistical frequency analysis as having potential for a burial ground. Today, Ferryland is a Newfoundland and Labrador Provincial Historic Site, and my cumulative 10 weeks there could be described as: lay out trench, dig for hours, sift your soil, complain about the rain, growl at the wind, look up with dirt on your face to see 10 tourists and a tour guide asking you to please talk about your research. Truthfully, when you’re excavating on a site like this half of what you do as the supervisor is talk with visitors about what you’re doing, while your crew is actually doing it. A lot of my units (1x1m squares) were partially dug by my volunteers while I gave mini-lectures on the grass.

I’m very clear when speaking to visitors that my goal for this project was not to exhume human remains, but to find evidence of burial shafts through soil staining left intact in the glacial subsoil. A lot of the people on the Southern Shore have been living in the area for generations and some of them might have ties back to those early settlers. Because I study burial landscapes and the spaces themselves, what I’m really interested in is seeing where the graves are compared to the town, how they are positioned, and maybe if they were building coffins for burial or not (you can sometimes tell from the width of the grave shaft). The soil in this area, I would explain to groups of tourists, is very acidic which means that organic material often doesn’t even survive 100 years, let alone nearly 400! Once I’m done my spiel, visitors often hang around to ask me additional questions, which turned out to be an amazing opportunity to engage with people about death and burial today, through a historic context!

The most common thing people would ask during both field seasons was ‘why are you digging so close to the houses?’ This, and other similar questions, opened up a really interesting dialogue about how we view burial spaces and dead bodies in society today, which was facilitated by the archaeological context before them. I got to tell people about how in the 17th-century, there were no funeral homes or crematories (and how they wouldn’t have been cremating good 17th-century Christians anyways), and that funerals were dealt with from the home, by the family and friends of the deceased. It was really an interesting experience to get to talk about these topics with the public however, and see them become a little more curious about engaging with the subject or mortality. The burial ground at Ferryland would likely not have been far away because they have to bring the body there themselves, and because they were scared of attacks from other European powers at the time it might have been seen as a security issue. There wouldn’t have been any issues with placing the dead near or in the settlement because they knew that a dead body was not a hazard to their health, and it might have been a comfort to know that their mortal remains were still close to the family. The historic dead still had an important role in their communities.

“A friend of mine rightly said death positivity is activism through archaeology.”

It was a wonderful experience to talk to visitors, hear their concerns with the dead being inside the community and how burial practices have changed in the last 400 years, and hopefully I did my part to dissuade a few of the myths around our dissociating with death in Western society. The 2017 excavation season just wrapped up a week or so ago, and I wish I could tell you where the graves are located but unfortunately we did not find them. This means either the graves at Ferryland are located somewhere in the minority of the statistical analysis results I conducted, or the graves have been destroyed through erosion, construction, or farming in the last 400 years. This means that while we don’t know where they are, the entirety of the archaeological site remains a burial landscape, and I think the interpretive potential there is very exciting. Win-win, really. A friend of mine rightly said death positivity is activism through archaeology. If my research and fieldwork can achieve one thing (maybe two things), it would be to learn through archaeology that it’s not morbid to talk about death.

Robyn Lacy is an archaeologist and illustrator, completing her MA in Archaeology at the Memorial University of Newfoundland. She currently studies 17th-century colonial burial landscape structure in North America. When she’s not standing in the middle of a cemetery assessing the slope and gravestone orientation, she can be found on a cliff somewhere rock climbing, or at home with her cats and partner, knitting up a storm.

If you are interested in following the progress of Robyn’s ongoing research and fieldwork, check out her Instagram, Twitter and her research blog: Spade and the Grave.

Leave a comment