By Dr. Christina Welch

Sex and death reflect the oppositions of immanence and transcendence, the earthy and the spiritual, the here-and-now and the ever-after. Culturally fascinating, the marriage of sex and death in Europe has a long history and one intimately tied to religion, and from sixteenth century onwards, also gender. This post explores a genre of art produced during this time period that melds these themes. It examines ‘Death and the Maiden’ artworks by Germanic proto-and early-Reformist artists who highlighted the folly, futility and transience of earthly vanities, through the use of erotic death imagery that juxtaposed an eroticized woman, who stood as a symbol of life and fecundity, with a male/masculine representation of death.

Paul Messaris in his book, Visual Persuasion, has suggested that visual images ‘make a persuasive communication due to iconiticy; the emotional response to the visual image presented’ (1997: viii-xv). Although a work on the role of images in advertising, I argue Messaris’ notion of iconicity can be applied to the proto-and early-Reformist ‘Death and the Maiden’ artworks. I argue that these eroticized representations of woman posed with a masculine image of death can be read through the changing lens of Christian notions of life, death, and the afterlife at a time when Roman Catholicism was challenged by Protestantism. In effect, I contend that to fully understand the ‘Death and the Maiden’ imagery produced by the proto- and early- Reformist artists Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Hans Baldung (alias Grien) (c1484-1545), Niklaus Manuel (Deutsch) (c1484-1530), and Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550), one must fully grasp their socio-religious context. Produced at a time when the central tenet of Roman Catholic after-life beliefs, purgatory, was being eradicated by Protestantism, these images state that ones focus should not be on mutable sensuous concerns, but on a reasoned Augustinian transcendence of the mind and the masculine trait of wisdom; they operated as Memento Mori (remember you will die) to remind those who had yet to Reform, that the after-life safeguard of purgatory could no longer save them from their sensual sins.

Purgatory was central to Roman Catholic theology, and effectively was a debtors’ prison where the souls of the deceased would reside until they had repaid their earthly sins. Purgatory was a place of severe and painful sufferance, a transitory kind of hell, although souls gladly accepted their punishment in expectance of the resulting unification with God. Time spent in purgatory varied according to the sinful nature of one’s soul, and certain acts conducted during one’s lifetime would give purgatorial remission, and this included the buying of indulgences. Further, prayers from the living could aid the dead in purgatory. Thus, at death, for the vast majority of people, the fate of the soul was not fully sealed. However, with the Protestant Reformation, the notion of Roman Catholic purgatory came into question and Reformers believed that salvation was by faith alone, and that the dead were responsible for their own sins, in their own lifetime. This shift in death beliefs can clearly be seen in the artworks of the proto-and early Reformists who worked in the ‘Death and the Maiden’ genre.

Firstly to Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).

Dürer was born a Roman Catholic and although it is believed he never totally abandoned his faith, he appears to have had Reformist sympathies. Dürer certainly had contacts with various religious Reformers despite being artist to the Holy Roman Emperor, and is known to have been sympathetic to Lutheranism. With the Reformist thrust toward individualism, it is of no surprise that in Dürer’s work we find the beginnings of a new ouvre of artistic representation of death; ‘Death and the Maiden’ – a woman alone with the predatory symbol of mortality.

Drawing on Augustinian thought (the predominate theology of the Reformation), Death was typically understood as male and connected to Adam, whereas life and lust was female and connected to Eve. In German, the language of these Reformist artists, the connection between death and the male is clear – Der or Herr Tod (Mr Death). Biblically death was brought into the world through Adam, and in Romans 5:12 Adam is clearly blamed for bringing sin and death into the world. Eve meanwhile brought life into the world (Gen 3:20) and the sin of sexual desire (Gen 3:16). But women also signified vanitas (transient life) and voluptas (earthly pleasure) and during this period in European culture, were typically perecieved as signifiers of wantage, of pleasure and the unruly, with contemporary works such as the Malleus Maleficarum (the Hammer of Witches), reinforcing the general social view that women were weaker in faith than men, and more carnal. Further, the Reformers firmly belived marriage to be blessed; with non-marital sex (including homosexual relations) bad for the soul, family, fortune, and honor. Indeed, Luther described the unmarried state as a poison to governement and the world; autonomous females were considered especially dangerous and we can clearly see this reflected in this drawing by Sebam Beham. Here Death is present at a ritual of female mutual masturbaton – a didactic image that represented normative notions of women as signifiers of unacceptable fleshly desire.

With women then as understood as symbols of life and lust in ‘Death and the Maiden’ images, and Death identified as male in this ouevre, we can move onto the explore the works of the three most significant Reformist artists of this genre, and explore the socio-religious politics of their images.

Niklaus Manuel (Deutsch) (c1484-1530).

Niklaus Manuel was a German-speaking Swiss religious reformer who used painting to express his political activism. Between 1515 and 1520 Deutsch painted a large fresco for the Bernese Dominicans in the tradition style of the ‘Dance of Death’. This mural provides the only erotic image of ‘Death and the Maiden’ in the ‘Dance of Death’ genre, and this fresco links Niklaus Manuel directly with the Reformation due to his attack on the ‘evils of the [Catholic] Church in the text [written] underneath’ the images; although the text does not go beyond the acceptable limits of the day.

Amongst these evils were the abuse of the mass, the belief in purgatory and the payment of indulgences. Notably, less than a decade after producing his fresco, Niklaus Manuel became a leading politician in Bern, where belief in purgatory was abolished in 1528. His political writings speak potently of his Reformist beliefs, including his assertions that lust, swearing and frivolity should not be tolerated. Indeed, he went so far as to state that ‘How fine a thing it would be if ye could so easily foreswear the world and recognise how greatly sin parts ye from God’(in van Abbe 1952b: 295).

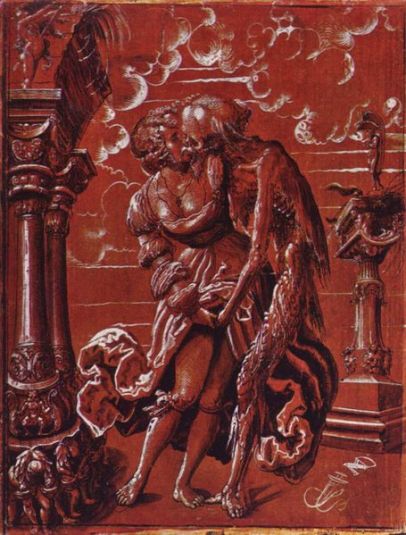

His Death and the Maiden (1517) engraving potently clarifies his feelings toward worldliness and pedagogically situates the vanity of beauty and the sin of lust. It demonstrates that humanity may have its tempting earthly pleasures, but at death we must each account for our sins before God, and therefore it is to the afterlife that we should turn our attentions.

The Bible preached simplicity and this was the key part of the Reformation movement, and for Niklaus Manuel his evangelical belief led him to give up his art and concentrate on following in the footsteps of Jesus, working for the poor and oppression; notably part of his work in public service included petitioning for an organized welfare state.

Further clarifying the link between individual sin in life, and a concern for death, is the work of the most prolific of the Reformist artists working in the ‘Death and the Maiden’ genre; Hans Baldung Grien (c1484-1545).

Most notable amongst Grien’s images are the Girl and Death (1517) and the Woman and Death (1519). As with Niklaus Manuel’s work, the young woman stands alone whilst death takes her; she is the symbol of Voluptas (pleasure) – young, beautiful, fleshy, in the prime of life, and essentially fecund. The association of Voluptas with Vanitas (the transience of life) is evident from the words above the 1517 image; Hie must du yu (Here must you go), but can be seen more clearly from his earlier representations.

Grien’s Three Ages of Women (1509-10) depicts the vanity of youth – the girl is ignorant of death (as is young woman in the 1515 drawing), whereas the older woman seeks to stave off Death’s hour glass (an artistic signifier of life’s transience). Notable here is the gendering of Death, with rag-like flesh in the place of genitals Death is obviously male, and indeed many of Baldung’s imagery from this time resonate with the Adam=male=Death/Eve=Woman=life link.

In these images of Grien’s we see the Fall, and there is a clear similarity between the positioning of Adam in these works, and the positioning of Death in the ‘Death and the Maiden’ imagery – both Adam and Death approach the female subject from behind. However, whereas Adam tends to caress, Death tends to grasp.

Perhaps of more significance in relation to the link is the metaphor of the bite. In all these Fall images Eve holds an apple, and Luther himself stated that ‘most people believe that [death] just happens… [but] Scripture teaches us that death comes… from the bite of the forbidden fruit’ (Luther in Kroener 1985: 77); in Latin Mors is death, whereas Morsus is bite, providing a literary and artistic pun.… the bite of the forbidden fruit brings the bite of death into the world. And this Adam and Eve/Death and Woman theme can also be seen in the last of our Reformation artists, Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550).

Beham was known as one of the so-called ‘godless painters’. In 1525 Beham was briefly expelled from Nuremburg for heresy against Lutheranism. With a personal theology based on the iconoclasm of Andreas Kalstadt (1486-1541), and the political and religious extremism of Thomas Muntzer (c1488-1525) – a leader of the Peasant’s War, Beham’s work potently reflected his radical religious Reformism. Each individual was responsible for his own sins, and it was the Fall that brought desire and death into the world. This was most clearly expressed in his 1541 work, The Hour is Over. In this image we are potently into the realms of arousal with his work deliberately placing the woman’s genitals centre stage, while Death grins lecherously. We have no choice but to be voyeurs here!

In 1547 he produced this woodcut, Death and the Standing Naked One which highlights the folly of vanitas. This image sums up Reformist art – ‘Renaissance woman’ may take centre stage: a beautiful, young, fecund individual surrounded by the glories of earthly materiality, but all these things will go to nothing when death annihilates her (and thus us).

So in the late-1500s and early-to-mid-1600s when Northern Europe was struggling with the transition between Roman Catholicism and its safety net of purgatory, and the Protestant Reformation when one accounted individually for earthly sins, we find this reflected in the socio-political expression of death and desire by proto-and early-Reformist artists. No longer could the living and the dead support each other to get out of the debtor’s goal, no longer a time where only the truely bad were damned to an eternity in hell, these artist represented the after-life beliefs of this new form of Christianity; a Christianity where only God knew where they went after death… should you die before atoning (and many people did die in this manner), then a bad death could mean a terrible afterlife.

Death was therefore a central concern, and thus the images stood as a reminder of vanitas to the social, political and religious elite, and they did so throuhg iconicyt. They were designed to remind one viscerally of human weakness, of the sin of earthly temptations, for ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God’ (Mark 10: 25). The maiden was a signifier for voluptas (pleasure), and of Eve whose desire for the forbidden fruit brought about sinful lust. These images were deliberately designed to arouse that lust and despite the fact that the maiden stands in front of Death, the meaning is that Death should be centre stage and the transcient pleasures of life, secondary.

Images

Fig. 1. Albrecht Durer. 1495. Young Woman Attacked by Death. Private Collection. Public domain via http://www.wikiart.org/en/albrecht-durer/young-woman-attacked-by-death-1495

Fig. 2. Sebald Beham. 1546-50 (reworked plate of Barthel Beham c1535-7). Three Nude Women and Death. Private Collection. Public domain via http://www.hans-sebald-beham.com/

Fig. 3. Niklaus Manuel (Deutsch). 1517. Death and the Maiden.Kunstmuseum, Basel. Public domain via http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Niklaus_Manuel_Deutsch_003`.jpg

Fig. 4. Hans Balding Grien. 1517. Girl and Death. Kunstmuseum, Basel. Public domain via http://www.abcgallery.com/B/baldung/baldung.html

Fig. 5. Hans Balding Grien. 1519. Woman and Death. Kunstmuseum, Basel. Public domain via http://www.abcgallery.com/B/baldung/baldung.html

Fig. 6. Hans Balding Grien. 1509-10. The Three Ages and Death. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Public domain via http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hans_Baldung_-_Three_Ages_of_the_Woman_and_the_Death_-_WGA01189.jpg

Fig. 7. Hans Balding Grien. 1519. Adam and Eve (Fall of Man). University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbour. Public domain via http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/baldung/adam-eve/adam-eve-1519.jpg

Fig. 8. Hans Balding Grien. c1512. Eve, the Serpent and Death. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Public domain via http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eve,_the_Serpent_and_Death

Fig. 9. Hans Sebald Beham. 1548. The Hour is Over. Staatliche Kunstammlungen, Dresden. Public domain via http://www.lamortdanslart.com/fille/fille_sebam.jpg

Fig. 10. Hans Sebald Beham. 1547. Death and the Standing Naked One. Staatliche Kunstammlungen, Dresden. Public domain via http://www.hans-sebald-beham.com/

Bibliography & additional reading

Broedel, H.P., 2003. The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft: theology and popular belief. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Harbison, C., 1976. Dürer and the Reformation: The Problem of the Re-dating of the St. Philip Engraving. Art Bulletin, 58 (3), 368-373.

Kroener, J.L., 1995. The Mortification of the Image: death as a hermeneutic in Hans Baldung Grien. Representations, 10, 52-101.

Messaris, P., 1997. Visual Persuasion; the role of images in advertising. London: Sage.

Purkiss, D. 1992. Material Girls: the seventeenth century woman debate. In: C. Brant and D. Purkiss, eds. Women, Text and Histories, 1575-1760. London: Routledge, 69-100.

Stewart, A., 1996. ‘Sebald Beham and Barthel Beham’. In: J. Turner, ed. Dictionary of Art, 3, 505-508.

Van Abbe, D., 1952a. Change and Tradition in the Works of Niklaus Manuel of Berne (1484-1531). Modern Language Review, 47 (2). 181-198.

Van Abbe, D., 1952b. Niklaus Manuel of Berne and his Interest in the Reformation. Journal of Modern History, 24 (3), 287-300.

Weisner, M.E., 2000. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe (2nd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weisner-Hanks, M.E., 2000. Christianity and Sexuality in the Early Modern World: regulating desire, reforming practice. London: Routledge.

Welch, C. 2014a. ‘Death and the Erotic Woman; the European gendering of mortality in times of major religious change’. Journal of Gender Studies 10.1080/09589236.2014.950557

Welch, C. 2014b. ‘Coffin Calendar Girls: a new take on an old trope’ Writing From Below Vol. 2(1) http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/ojs/index.php/wfb/article/view/471

Dr Christina Welch is a senior lecturer in Religion at the University of Winchester where she leads the Masters degree in Death, Religion and Culture. Her research concerns the intersections of religion with visual and material culture. As well as writing about Death and the Maiden, she is currently researching late-Medieval English carved cadaver memorials. She crowdfunded the money to fund the materials for a new wooden cadaver to be carved by Eleanor Crook, an anatomical sculptor; this will be the first time in over 450 years that something like this has been sculpted.

Details on the project can be found at http://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/guy-the-gaunt

Leave a comment