Death is the kind of thing that sneaks up on you, even when you think you are prepared, and renders you speechless and lost—not knowing what to do next or how to act. In that situation, having a caring, knowledgeable person to sit with your loved one when you are exhausted, to help you learn the signs of impending death, to answer your questions about what is happening or how to make your father, partner, grandmother, child more comfortable, and how to make the most of those last days or hours is nothing sort of invaluable. That is the goal of the end of life doula.

– Evi Numen –

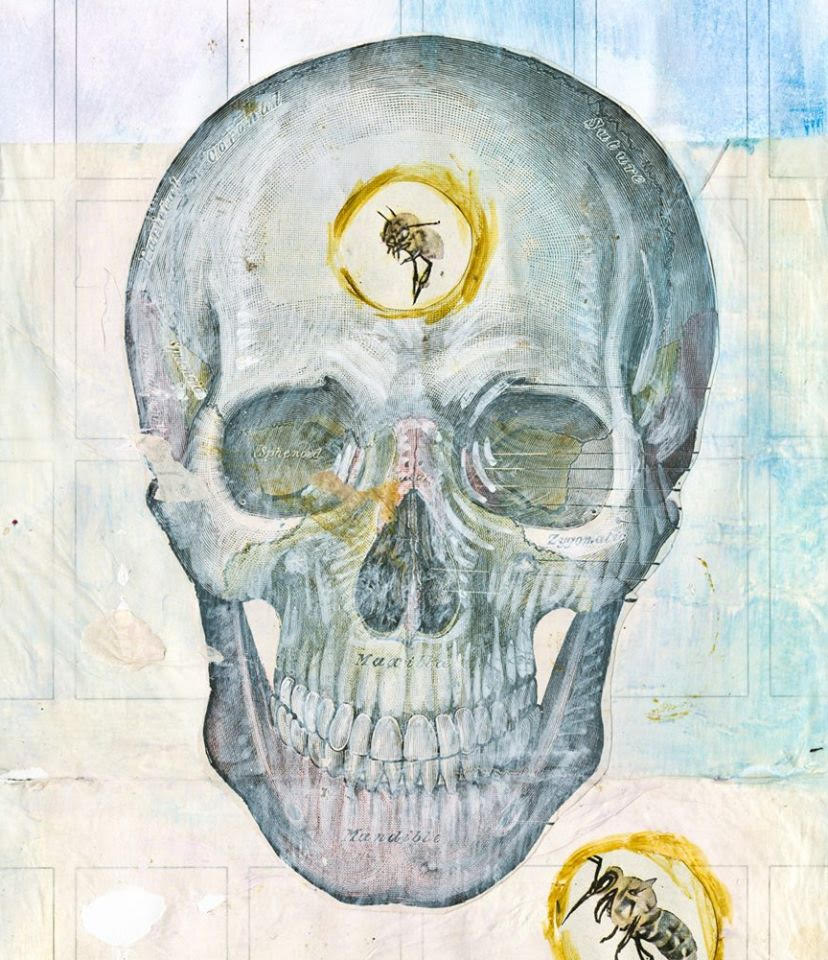

Evi is a visual artist and independent researcher from Athens, Greece who is based in Philadelphia. She is the Exhibitions Manager & Designer of the Mütter Museum and is currently training to be a death midwife, Evi recently launched a new online curation website today at thanatography.com featuring contemporary mourning and memorial art. She is a history of medicine enthusiast with a particular interest in instrument design, cadavers, and psychiatry.

Death brought us together.

There was a sense of gravity in the air and yet a palpable elation, as if something momentous was about to take place. The workshop was tucked into an unassuming meeting room in a chain hotel in a New Jersey city that clearly existed around its expo center. I didn’t know what to expect when I walked into that meeting room. I sat down near the front, notebook and pen in hand. I would soon find out that the people in the room came from drastically different backgrounds. Behind me sat a massage therapist, on my right an atheist student and actor, behind him a long-haired Buddhist practitioner, next to me a Christian pastor. A few were hospice volunteers and palliative care nurses, already entrenched in care for the dying. Others, like me, had never worked with the dying, and came in answer to a calling they did not expect to get.

I had been looking into death midwifery for about a year or two, since I first heard of the practice through the Order of the Good Death. When I stumbled across the INELDA training event online something clicked. It was just a week away in New Jersey, a few miles outside of Manhattan, a distance I could travel easily. I stayed up at night wondering if this was right for me—whether I could do this. Ultimately, there was only one way to found out what I could handle and what I couldn’t. What does a death midwife do, anyway?

The workshop leader, Henry Fersko-Weiss, began the workshop by answering that very question. Like a birth midwife, an end of life doula serves to guide the dying person and their family through the death process, as one would in the hours leading up to and during a birth. Unlike the death process, most of us know the basics of the process of pregnancy and birth, at least in theory. We know what crowning means, or what it means when someone’s water breaks, even how contractions change nearing a birth. The human reproduction and gestation process of humans is common knowledge. Not everyone experiences a birth other than their own, but all of us will experience death and grief. And yet we know so little about the natural process of death, let alone how to guide someone through it.

This is the gap that Henry Fersco-Weiss hopes to fill. Trained as a social worker, a hospice worker and a birth doula, Fersco-Weiss drew on his knowledge and experience to create a model to train volunteers to guide the dying and their loved ones through that undoubtedly difficult and very hectic time. After teaching the model through the holistic education Open Center in New York and local hospices, he founded the International End of Life Doula Association, along with Meredith Lawida and Janie Rakow, to provide a professional association and certification for the emerging field. I was participating in the inaugural Certified Vigil Doula training class.

The INELDA model is tiered; vigil doulas report to a “Lead Doula” who makes first contact with the family of the dying patient, through a hospice, and communicates with them to plan the vigil and define the ways the patient and the family can make their last days together meaningful, loving, and more comfortable. The lead doula organizes the shifts of the vigil doulas and takes care that the vigil plan created for the patient is honored. She is tasked with educating the family about the dying process and its symptoms, as well as teaching them ways to alleviate the patient’s fears, pain, and discomfort. She urges the family to address their own regrets, fears, and worries, and helps them create a space of reminiscence, respect, and care. The vigil doulas on the other hand take shifts at the patient’s bedside during the last phase of the dying process, making sure that he is always attended to and allowing the family members to rest and process the event.

Death is the kind of thing that sneaks up on you, even when you think you are prepared, and renders you speechless and lost—not knowing what to do next or how to act. In that situation, having a caring, knowledgeable person to sit with your loved one when you are exhausted, to help you learn the signs of impending death, to answer your questions about what is happening or how to make your father, partner, grandmother, child more comfortable, and how to make the most of those last days or hours is nothing sort of invaluable. That is the goal of the end of life doula.

Too often, in the drive and effort of the doctors to try this one last experimental treatment or that of the family to “not give up,” the dying stage becomes almost an afterthought—or the subject no one wants to discuss out of unspoken fear or superstition. The family may plan for entering hospice care and the burial or even discuss the estate of the soon-to-be deceased, but rarely the interim time of death itself.

This past spring, my mother’s best friend was dying from cancer, an indirect result of exposure to Agent Orange when he was in Vietnam. A shadow of his former self, in tremendous pain and yet trying to hold on, he tried to appear strong for his family. He struggled between terrible agitation and delirium, with brief flashes of clarity, the insights from which were lost to him in the blink of an eye. We all held on to hope, not wanting to broach the inevitable truth that there was no point in further treatment or tests, in wasting time looking into the next painful treatment option. I look back with regret, wishing I had the knowledge then that I do now to say, enough—let us be. Let us spend the little time that we have to reminisce and hug and say goodbye, away from the incessant beeping of the machines and the awkward exchanges with overworked doctors who don’t have the energy to say a compassionate word.

“We are all dying this very moment, just not actively,” quipped Henry. I never realized what a long, intricate process dying is. Every cell, and eventually every system in your body begins to die. Your circulation falters, your breathing patterns change, your nervous system breaks down.

This past summer, a loved one’s mother passed away. Her daughter described the large red splotches that appeared on her face a day or two before her death. She was really distressed to see that and even questioned her mother’s diagnosis. She didn’t know that mottling was a symptom of the dying process and a sign of imminent death. Neither did I. I wish I could have told her that what she was seeing was natural.

When I tell people that I’m training to become a death midwife, they inevitably ask why. Nearly 12 years ago, my partner was killed in a terrible car crash, when the car he was driving hit black ice and spun off the road, crashing into a coil around a utility pole. I survived, with half a dozen broken bones and the deep, primal fear of losing a loved one.

The problem with death is that nobody gets to escape it. We all die, and sooner or later we all lose those we love. Yet I spent the decade following the car accident, in various degrees of apprehension that my current partner could die in any moment, even gripped by middle-of-the-night anxiety that woke me to check if he was breathing. Slowly the intensity of my fears subsided and gave rise to a simple realization: I had to confront death. I had to understand how it happens, how to respond to it mindfully, and how to help others do so as well.

Death brought us all together.

Every person in that small meeting room had experienced a death that changed their life, their perspective, that ultimately changed who they are. Some had deaths in their lives they were struggling to comprehend. Others wished their loved one had a better death. Still others wanted to built on what death had taught them. During those 22 hours of the training, spread across three days, we learned, laughed, and cried. We hugged each other and shared stories or emotions we had never shared before. Not among strangers anyway, but were no longer that. We had all gained new names and stories. We all bore a list of losses that spun around and encircled us, each name representing a reason why we were there, a reason to do this.