S Elizabeth interviews musician Gemma Fleet of The Wharves on her project “Lost Voices” which explores vocal improvisation in folk culture. Volume 1. “Keening and the Death Wail” has roots in Fleet’s own childhood. She believes she encountered an Irish traveler funeral; an “unhindered display of grief” wherein the woman in mourning was not being hushed, but instead comforted by family and loved ones whose wails and cries joined in with her own.

– S. Elizabeth –

S. Elizabeth is a fancier of fine old things, nostalgic whimsies and magics both macabre and melancholy. She is a shadow seamstress, star stitcher, word witch and weaver of the weird. She currently lives among the mosses and swamps, enjoys her coffee a great deal, and is a friend to all felines.

You can follow S. Elizabeth on Twitter @mlleghoul

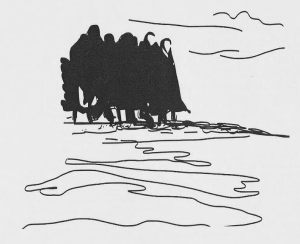

The death wail is a keening, mournful lamentation, usually performed in ritual fashion soon after the death of a member of a family or tribe. Examples of death wails have been found in many societies, including among the Celts and various indigenous peoples of Asia and Africa, as well as with Indigenous Australian peoples.

In old Ireland, the practice of keening (caoineadh, in Irish, meaning to weep) or crying for the dead, is a tradition which is associated almost exclusively with women and is an integral part of the Irish wake ritual. A professional keener was often hired by a family as a way of honoring the dead; this bean chaointe (keening woman) inhabited a liminal state between the living and the world of the dead during the mourning period, and entered a kind of “divine madness” which “allowed the keener to express the collective outpouring of grief through her voice and body, leading the community in a public expression of sorrow and lament.”

Voices is a project which explores vocal improvisation in folk culture, and Volume 1. Keening and the Death Wail, is a 31-page booklet and cd of audio examples released by Susan Records in November of 2015, and which delves into the history and the art of keening. The author, musician Gemma Fleet of The Wharves, writes authoritatively and evocatively on this ancient, traditional art of lamentation as it relates to the Irish funeral and other cultures worldwide, as well as tackling it from a feminist perspective, and how it ties into the grieving process.

The booklet opens on a personal note, wherein Fleet recounts compellingly how, when she was younger, she believes she encountered an Irish traveler funeral; an “unhindered display of grief” wherein the woman in mourning was not being hushed, but instead comforted by family and loved ones whose wails and cries joined in with her own.

Gemma graciously gave of her time to answer a few questions about this fascinating and dramatic mourning tradition, and it is with this memory that we begin.

What was it, that prompted you In 2015– twenty years after you first heard the lamentation of that Irish traveling funeral– to begin this project?

I came across a video of the Greenham Women protesting in parliament square , they were dressed in black and keening. The sound brought back the memory of the funeral I had witnessed all that time ago and prompted the research. For me, certain sounds evoke a rush of emotion and hearing that sound again it was like I was there.

Where does one go to find information on these ancient traditions? Who did you talk with and how did you find out about them? How did you go about gathering data on oral traditions in languages that are barely spoken anymore?

I am lucky enough to be in a band with a Gaelic speaker (Dearbhla Minogue from the Wharves) we looked at some of the songs and translated bits, the Gaelic used was very old and hard to translate. I also spoke to some work colleagues from Ghana and Croatia who have similar practices, they were interested in the project as we were working in a music therapy centre at the time so understood my interest. Other than that I talked to family members and carried out research in many libraries in England, Ireland, Canada and the US. I found some of the older books easier to find in the US funnily enough, stories from Irish immigrants who continued traditions.

Where did you find the audio extracts? How did you feel, listening to them? I realize that it’s a strange question, “what is your favorite death wail?” but were there any amongst the ones you featured that you were particularly struck by or that resonated with you?

My favourite tracks are the ones we recorded, the feeling in the room was strangely melancholy as we started to vocalize and think about keeners, other clips I got from a variety of places including a BBC radio 4 programme from the eighties that seemed to have some very rare clips from the producer’s field recordings.

You state that “Using music and poetry, as any musician will tell you, can relieve and give space to feelings that cannot be appropriately discussed with dialogue”: I’m keenly interested in how, as a musician yourself, this project and all that you have learned on the subject may have affected your own music?

The project prompted me to create a song called ‘My Will’ with the band The Wharves, we used the improvisations recorded with a mixed group of women (even including one heavily pregnant woman) to start the song, it’s a song about community spirit and feeling supported through tough times by other women.

Keening wasn’t just an art form, you also speak to important feminist implications with regard to these lamentations and death wails. You state that “participation in funerals allowed women to express themselves in the public domain and challenge the social order as the authoritative figure in the funeral ceremony.” Keening as a form of protest comes up in your writing as well. Can you elaborate on these ideas for us?

Being given the space to express oneself unbridled can be therapeutic, artists often need to release feelings of protest and injustice . For me these keening women, as well as expressing their grief were expressing their feelings about other things. I see them as early performance artists or musicians exposing themselves and paving the way for allowing other women to express themselves which is fundamentally feminist. Much like when people are inspired by contemporary outspoken women, it’s like Laurel Thatcher Ulrich states: ” well behaved women seldom make history”

The last part of your book is a nod to Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s Theory of the 5 stages of grief. How do you think this ancient tradition accommodates these stages of mourning?

I don’t think there are any ‘rules ‘ to mourning , the Kubler Ross theory as a basis identifies certain behaviours. I feel the act of keening gives room for expressing anger, confusion and sometimes mania that comes from loss where a funeral the typical western sense is usually somber and , in my experience, rushes of unbound emotion subdued.

Leave a comment